Tomorrow Everything Will Be Alright

An intense conversation between two people one evening leads to a pictorial love story about loss and longing. An homage to Eric Rohmer and the attention he paid to the tiny details of our everyday lives.

Interview with Akram Zaatari

What is cinema for you Akram?, was the first thought, that came into my mind, when i watched TOMORROW EVERYTHING WILL BE ALRIGHT for the very first time. In two three lines - even less or much more - as you wish & please give us a description of your ideas.

Making films is certainly different from watching them or living with them around. As a filmmaker, you communicate your universe through a language that you develop from film to another like an architect builds one building after another. With every new work you feel you have gone further, and you get to see something you weren‘t aware of before. You communicate your favorite themes, plot your favorite situations, and sometimes use the same actors who appear and reappear in films; what I designated as your univer se. But as audience, you live with films differently. They make your universe and become an extension to your life, they affect your habits and with time, they reference your life. How? Mainly by moving you “emotions“. I believe much of our behavior, our desires are conditioned by films and literature. We live alone even if we make families and friends, and films help us overcome our loneliness. I grew up in very difficult moments in South Lebanon, and later in my teens I moved to Beirut and films and literature were my only way to imagine life elsewhere, to imagine love elsewhere, and to get to accept your difference. I remember many instances in Beirut in the eighties when I was watching a film alone in a huge old theater. TOMORROW EVERYTHING WILL BE ALRIGHT was made as a response to a call by ICO and Lux in London to filmartists to make short works that would screen prior to feature films in commercial movie theaters across the UK. Prior to that, none of my films had screened in commercial movie theaters. It was an occasion to make a work for cinema, about cinema. What else than a love story! There is something romantic about Love stories and screen, and no matter how stereotypical this can be, love stories remain so dominant in film history.

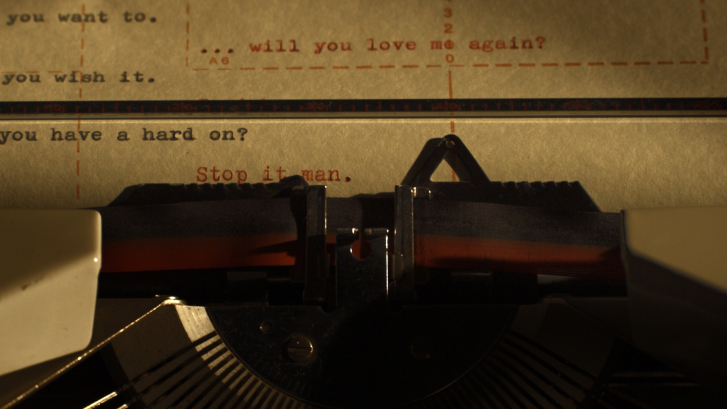

You recreate a physical body via the abstince. You recreate a history via the written word- When did you know, that all of the moving image in this film would be the typemaschine moving the paper upwards?

TOMORROW EVERYTHING WILL BE ALRIGHT is about a chat between two former lovers: two men, who were separated ten years ago, and who confess to each other their desire to meet again. I have to admit that I shot the film twice, once with super 8 black and white stock, but I didn‘t like the look. So I shot it again with RED. In the first Super 8 version I shot a scene at sunset with 2 young men, one of them having his hand bleeding. It was supposed to be the final scene. Although I love it, and the way it came out on film, I decided not to repeat it when I shot again with RED. Slowly the film was settling as one without the physicality of actors, and the two characters on the chat became like ghosts that could take the faces of anyone the audiences like to recall. It is inevitable in Love story classics that audiences get attached to actors. It is nice when- after you watch a film- you go back home with a face in mind, a body and an unsatisfied desire to be with that person. It is this desire that I wanted to try and reproduce without using human subjects. The typewriter I used featured in many of my photographic works. It is the typewriter that my father gave me when I turned 16. Using it today, is using a device that belongs to the early eighties, with a logic that belongs to the internet age. It produces something extra real, like the ghostly presence of the absent actors. The traces of their talk is registered like a log sheet that scrolls up when more is said. It‘s the logic of online chat, but it is also how you write a script, so transforming a situation into a log/dialog list can be seen as stripping cinema from its actors, from mise en scene, but it is also bringing back cinema to its origin, the written script.

You live and work in Beirut. How much does the political situation and the circumstances influence your work?

Living through the many wars in Lebanon probably had an impact on me, particularly politically. I took art as a territory through which I produce work. I am a total pacifist, and I do not romanticize revolutions. I would like to believe that the left can still make our life better, but it doesn‘t seem to be possible. Lebanon left me with a big disbelief in people deciding their own fate. I would like to stay away from power.

(Maike Mia Höhne)

details

-

Runtime

7 min -

Country

Lebanon, Great Britain -

Year of Presentation

2011 -

Year of Production

2010 -

Director

Akram Zaatari -

Cast

-

Production Company

Akram Zaatari -

Berlinale Section

Shorts -

Berlinale Category

Short Film

Biography Akram Zaatari

Born in Saida in the Lebanon in 1966, he studied architecture at the American University in Beirut. After graduating he took up studies at the New School for Social Research in New York where he graduated in media studies. He worked at Future Television in Beirut from 1995-97 and made numerous videos. The founder of the Arab Image Foundation, he lives and works as an independent filmmaker in Beirut.

Filmography Akram Zaatari

2015 Thamaniat wa ushrun laylan wa bayt min al-sheir